The Quiet Alchemy of Spalted Wood: How Decay Becomes Beauty

Discover how spalted wood forms, why makers prize it, and how controlled decay transforms storm-fallen hardwoods into stunning, functional art.

CARVING PROCESS

11/28/20255 min read

The first time I ever split open a truly spalted log, I remember stopping mid-swing. The inside looked nothing like the quiet, gray bark on the outside. Instead, the heartwood was alive with ink-like strokes—dark, wandering lines that twisted and intersected like a map drawn by a very patient artist.

You can carve for years before finding spalting at the “just right” moment. When I opened Spalted Maple Log #1, I knew instantly the tree had written its own story long before I started mine. The patterns were mature but not overrun, bold but still crisp, and—most importantly—held enough structural strength to carve. It felt like stumbling onto an artists' collaboration I hadn’t realized I was part of.

Spalted wood gives you the sense that nature has already begun shaping the piece, and you’re simply framing her work of art.

Where Spalting Really Begins

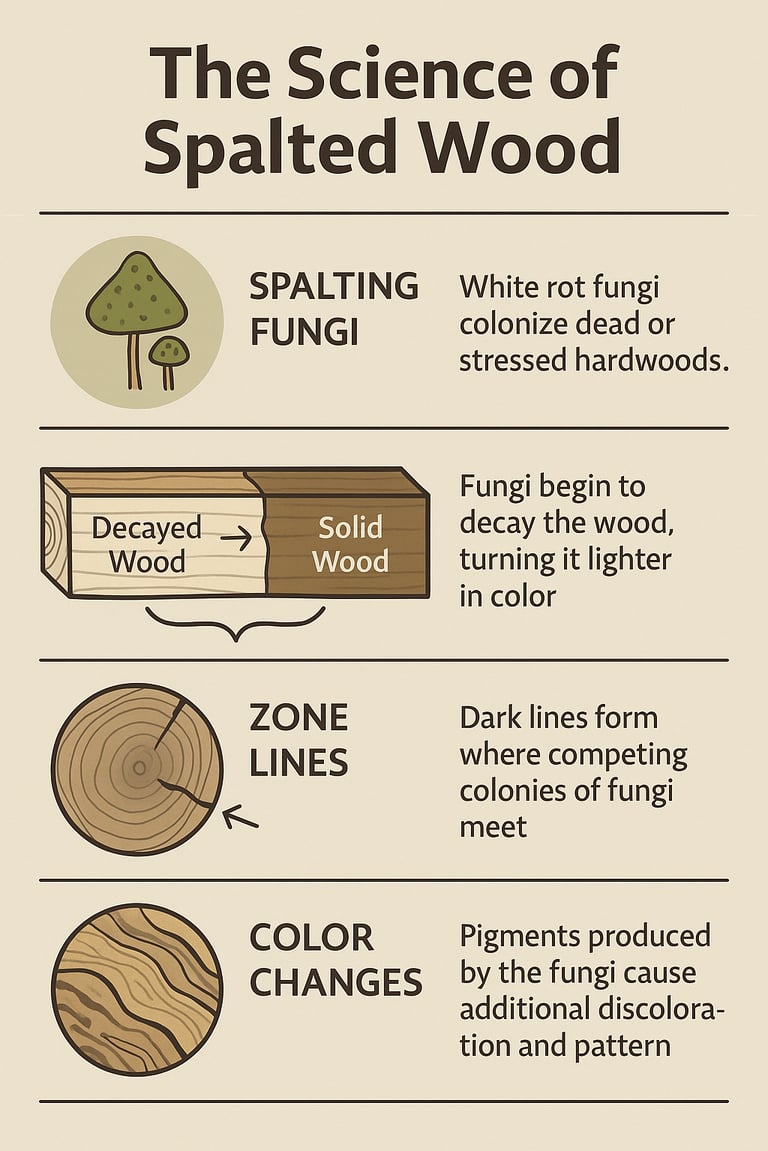

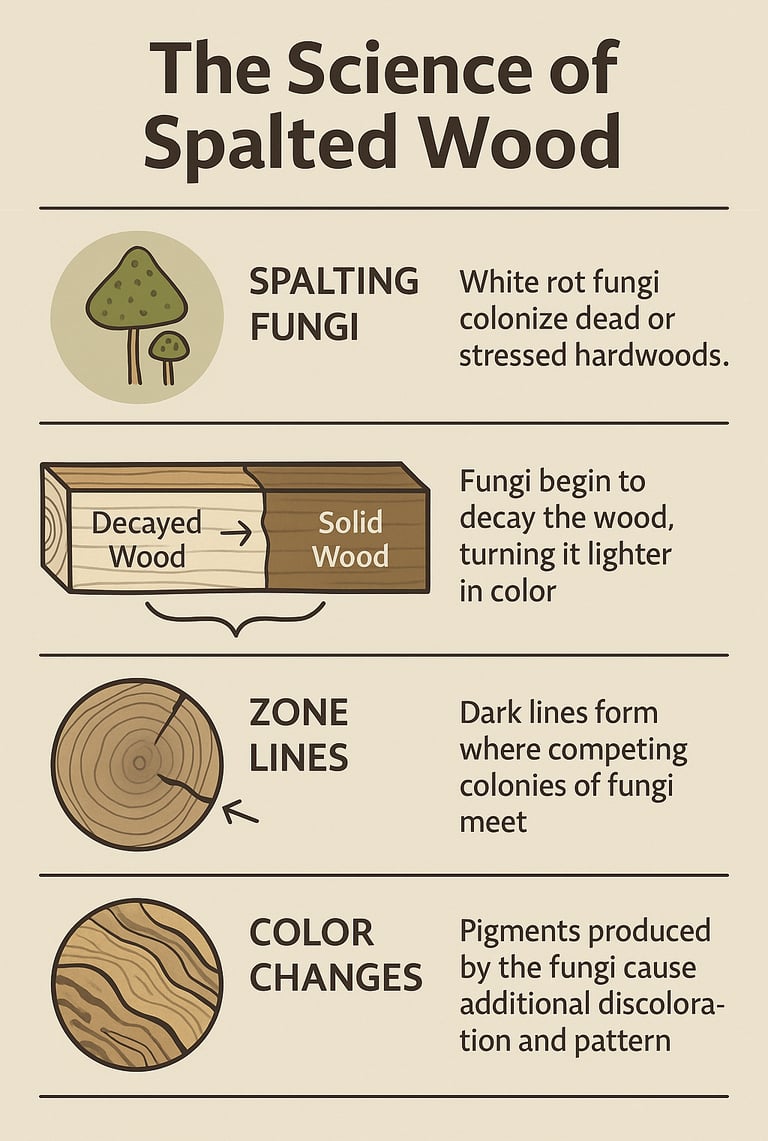

Spalting doesn’t start in the workshop (though many try to recreate the alchemy there!). It starts quietly, out in the world—often with a fallen limb, a bit of moisture, and the first invisible threads of fungal life moving into the wood.

These fungi aren’t villains. They’re part of the natural recycling system that breaks down fallen trees so nutrients can return to the soil. As these organisms move through the log, they create subtle shifts in color—pale washes where lignin has softened, or warm browns where the wood has begun to change.

And when two fungi meet?

That’s where the magic happens.

The bold, dark “zone lines” that spalting is famous for are territorial boundaries. Two colonies collide, defend their space, and leave behind a line of pigment that looks like ink poured into the grain. Sometimes those lines sweep gracefully through the wood. Sometimes they fracture into sharp geometric angles. Every log is different.

Hardwoods like maple, birch, and beech reveal this process with the greatest clarity. Their vessel structure—the tiny tubes that once carried water—creates a canvas that captures contrast. Softwoods can spalt too, but their uniform cellular structure makes the patterns softer, blurrier, and often less striking.

The Narrow Window Between Beauty and Breakdown

There is always a moment—an exact moment—when spalted wood is perfect for carving. Too early, and the patterns haven’t formed yet. Too late, and the wood begins to crumble. That late stage is called “punky,” and it feels almost like wet cardboard under the knife.

Judging where a log falls on that spectrum is equal parts experience and intuition. Sometimes a log looks decayed from the outside but is richly patterned and firm inside. Other times, a piece that seems promising reveals itself to be too soft to use.

Working with spalted wood feels a bit like foraging: you become attuned to the small signs. The weight in the hand. The sound the hatchet makes. The way fibers separate during splitting. You learn to notice the slight give of softening wood… and the satisfying resistance that means the structure is still intact.

This is why pieces from a single log—like the ones in my Storm Drop Collection—feel like siblings. They come from the same moment of the tree’s life, frozen just before its structure yielded to nature’s final reclaiming.

Is Spalted Wood Safe to Use?

This is a question customers ask more often than anything else. The patterns are beautiful—but the idea of “fungus in the wood” can unsettle people who haven’t handled it before.

Here’s the simple truth:

Spalted wood is safe when it is dry, stable, and finished properly.

The fungi that create spalting stop growing once the wood dries. By the time it’s carved, cured, burnished, and finished with a food-safe oil, the wood is no different from any other hardwood utensil—except that it carries a story in its grain.

It’s no riskier than blue cheese or sourdough starter, both of which rely on microbes to create something wonderful. Nature’s chemistry is everywhere. Spalting is simply her artwork.

Why Makers Value Spalted Wood

Ask any woodworker why they enjoy carving spalted wood, and the answer usually comes down to a mix of challenge and character. Spalting introduces variation—firmer patches next to softened areas, lines that shift direction, moments where the grain asks you to slow down and pay attention. It’s not difficult in a frustrating way, just in a way that reminds you that this material has already had a life of its own.

Those natural zone lines often guide the shape. If a line sweeps through the center of the billet, I may place the spoon bowl right where that contrast will shine. If the spalting is concentrated near one edge, I might use that area for a handle so the pattern is visible without compromising strength. The wood tells you what it wants to become, but in a practical, intuitive way—not a mystical one.

What makes spalted pieces enjoyable for customers is the same thing that makes them interesting to carve: no two look alike. Even utensils carved from the same log share similarities but not identical patterns. Spalting gives each finished piece a clear sense of origin—evidence of how the tree aged, how the fungi moved through it, and how the carver responded to what was revealed in the grain. The result isn’t dramatic; it’s simply honest and authentic. The wood shows where it has been, and the final shape respects that.

Final Reflection

Spalted wood invites us to look at aging differently. Decay isn’t always destruction; sometimes it’s transformation. Sometimes it’s a reminder that even as nature breaks things down, she leaves something behind that is unexpectedly beautiful.

When I carve from a spalted log—especially one like the storm-fallen maple in my neighborhood—I feel like I’m participating in that transformation. The tree lived its life, the fungi added their marks, and I get a small say in the final form.

It’s a collaboration across time, and the result is something both humble and extraordinary: a simple wooden utensil carrying a history of wind, weather, fungi, and human hands.

Want to Learn More About Spalted Wood?

If the world of spalting has you curious, there are some excellent places to explore the craft, the science, and the ecological story behind these patterns:

🌿 Dive into the science of spalting with Oregon State University’s Wood Science & Engineering Department — Their research into fungal pigmentation and zone-line formation is some of the most detailed available, and offers a fascinating look at the biology behind spalting.

🪵 Explore the Forest Products Laboratory’s guide to producing spalted wood —

This short technical guide from the USDA Forest Products Laboratory explains how spalting forms, which fungi create zone lines, and how woodworkers can identify safe, structurally sound pieces. It’s one of the clearest research-backed overviews available for anyone interested in the craft and science behind spalted wood.🔬 Read USDA Forest Service materials on wood decay and fungal ecology — These publications explain how fungi move through fallen trees, why certain species spalt more dramatically, and how environmental factors shape the appearance of spalted wood.

🥄 Visit the Spoonweather shop to see how I use spalted wood in practice — Each piece carved from storm-fallen hardwoods carries its own patterns, and spalted pieces are always among the most unique in the collection.

If you enjoy the mix of science, craft, and storytelling behind spalted wood, you’re in good company. It’s one of those rare materials that teaches you something every time you work with it—and reminds you that beauty often begins long before the carving ever starts!

If you’d like to follow along, I also share stories, spoons, and resources regularly on Instagram @spoonweather_carvings.

Spoonweather

Hand carved wooden spoons honoring local trees and community. Made in the USA .

© 2025. All rights reserved.

Learn more

Navigate

Connect

Needham, MA