What Trees Do During the Winter (A Look Inside the Quiet Season)

Winter forests may look still, but trees are actively managing energy, water, and timing beneath the bark. A clear, accessible look at winter tree biology, the steady rhythm it reveals—and the lessons it offers for our own lives.

BACKGROUND & HISTORY

1/13/20265 min read

Winter changes how a landscape looks and how it feels. Leaves fall, growth stops, and forests seem to quiet down. But that quiet isn’t emptiness. It reflects a shift in rhythm. Trees move from a season of outward growth to one of preservation, protection, and preparation. The pace slows, but the work doesn’t stop.

Once you understand what’s happening inside a tree during winter, the season stops feeling like a pause and starts looking like an essential part of the cycle.

A Slower Mode, Not a Shutdown

When deciduous trees lose their leaves, photosynthesis and visible growth come to an end—but the tree itself remains very much alive. Cells continue to respire at a reduced rate. Basic maintenance and repair still happen. Roots remain active whenever soil temperatures allow.

What changes most is movement and pace.

In summer, water moves upward through a tree because leaves are constantly losing moisture to the air. That evaporation creates a pull that draws water up from the roots—a process called transpiration. In winter, that pull disappears. Water doesn’t stop existing in the tree, but it no longer rushes upward. Instead, moisture remains distributed throughout the wood and roots, shifting slowly in response to temperature changes.

Most mature trees have roots that extend below the frost line, where soil temperatures remain relatively stable even in winter. During mild spells, those roots can still absorb water. That slow uptake helps keep living tissues hydrated and reduces stress during long cold periods.

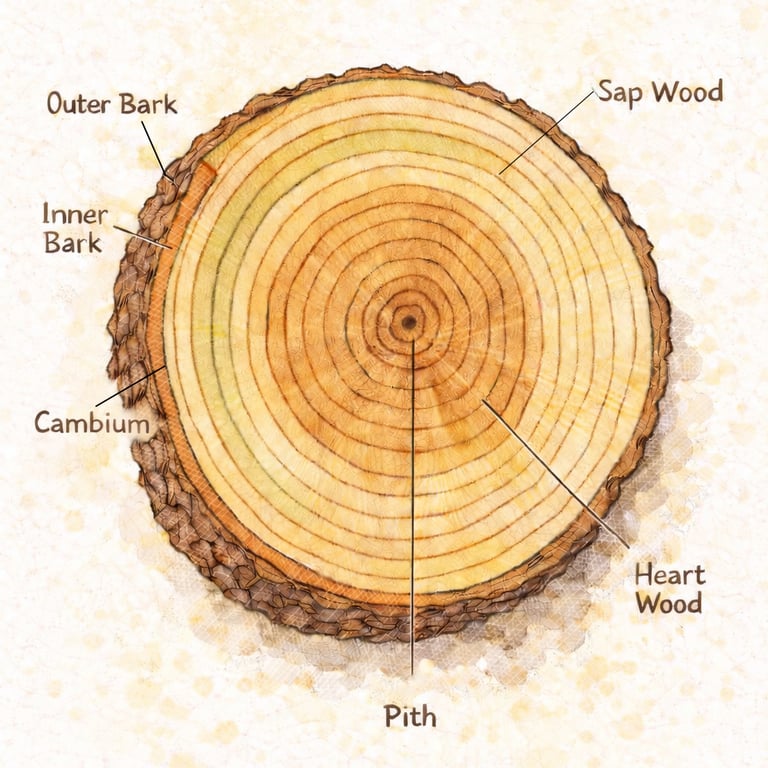

However, growth largely comes to a standstill. The thin layer of cells responsible for adding new wood called the cambium shuts down on purpose. Producing new cells in freezing conditions would result in weak tissue. Winter isn’t for building—it’s for holding steady.

Winter as a Reset for Pests and Disease

One of winter’s most important roles in a tree’s life has less to do with cold tolerance and more to do with long-term health.

Insects, fungi, and bacteria thrive in warm, moist conditions. During summer, trees are constantly managing small injuries, sealing off wounds, and producing chemical compounds to slow decay and infestation. Cold temperatures dramatically reduce these pressures. Insect life cycles pause. Fungal growth nearly stops. Decay organisms that spread quickly in warm months become dormant.

Forest research has shown that sustained cold winters significantly reduce overwintering insect populations, which lowers pest pressure during the following growing season. Without that annual interruption, populations can build year after year, placing trees under increasing stress.

Winter also gives trees time to strengthen internal boundaries around damaged areas. Trees don’t heal wounds the way animals do; they compartmentalize them. By isolating injured tissue and reinforcing internal barriers while biological threats are low, trees enter spring in a more stable condition.

Winter doesn’t just slow things down—it restores balance.

The Rhythm Carries Into My Workshop—and Beyond

There is a rhythm to how trees move through the year. Growth doesn’t happen all at once, and it doesn’t happen continuously. It’s shaped by seasons of expansion followed by seasons of restraint—times when the work is visible, and times when it’s mostly internal.

I feel that same rhythm in my work as a spoon carver.

The weeks after the holidays often look quieter from the outside. But like the forest in winter, this is not idle time. It’s a season of steady, intentional work—carving, finishing, and building toward the months when everything speeds up again. Spoons take shape one after another. Small refinements add up. Inventory grows quietly.

What I appreciate most about winter trees is how deliberately they use this phase of the cycle. They slow growth, reinforce what already exists, reduce unnecessary risks, and wait until conditions are right to move forward again. That pattern feels relevant well beyond trees or woodworking.

Winter—whether literal or figurative—offers space to regroup, repair, and prepare. It’s a reminder that not every productive season looks busy, and not every quiet season is a setback. Sometimes it’s simply the part of the cycle where strength is rebuilt and direction becomes clearer.

Trees don’t rush their cycles, and they’ve been at this far longer than we have. Winter shows us that preparation matters, timing matters, and that quiet work done at the right moment often makes the next phase possible.

When spring arrives and everything accelerates again, both the forest and the workshop are ready—not because of a sudden burst of effort, but because of quiet, steady work that had been unfolding all along.

Stored Energy and the Shift from Starch to Sugar

Trees prepare for winter months in advance. During spring and summer, sugars produced in the leaves are converted into starch and stored throughout the tree—especially in the roots, trunk, and inner wood.

As fall progresses and temperatures drop, the tree’s internal balance shifts. Cooler temperatures and changing daylight alter hormone signals inside the tree, which in turn change which enzymes are most active. Enzymes that build starch slow down, while enzymes that break starch apart become more active.

Starch is gradually converted back into simple sugars like glucose and sucrose. These sugars dissolve easily in water, lowering its freezing point and helping cell membranes stay flexible. Instead of freezing hard and rupturing, cells can tolerate cold by gently dehydrating and re-hydrating as temperatures fluctuate.

This conversion happens slowly, over weeks. Trees that experience sudden early freezes before the process is complete are more likely to suffer damage.

This chemistry also explains a familiar winter phenomenon: maple syrup! Sugar maple trees store large amounts of starch during the growing season. By winter, much of that starch has converted into sugar, loading the sap with sweetness. In late winter, when nights freeze and days thaw, pressure changes inside the tree push that sugary sap upward. The sugar collected in spring wasn’t made then—it was produced the previous summer, transformed in fall, and held in reserve all winter.

Timing Growth: Buds and Rings

Bare winter branches may look empty, but they carry next year’s growth in plain sight. Along each twig are buds containing fully formed leaves or flowers, created during the previous growing season and sealed inside protective scales.

Those scales reduce moisture loss and buffer temperature swings. Many tree species also require a certain number of cold hours before buds are allowed to open. This built-in delay prevents a warm spell in midwinter from triggering growth that would almost certainly be damaged by the next freeze.

Tree rings reflect this same sense of timing. In spring and early summer, growth is fast. Cells are larger, walls are thinner, and water moves freely. As the season winds down, growth slows. Cells become smaller, walls thicken, and the wood packs more tightly together, forming the darker band at the edge of each growth ring.

Winter itself adds no wood at all. It is the intentional pause between growth cycles—the space that allows the next season to begin cleanly.

Beech tree winter leaf buds as seen in January

Typical cross section of a tree

Spoonweather

Hand carved wooden spoons honoring local trees and community. Made in the USA .

© 2025. All rights reserved.

Learn more

Navigate

Connect

Needham, MA